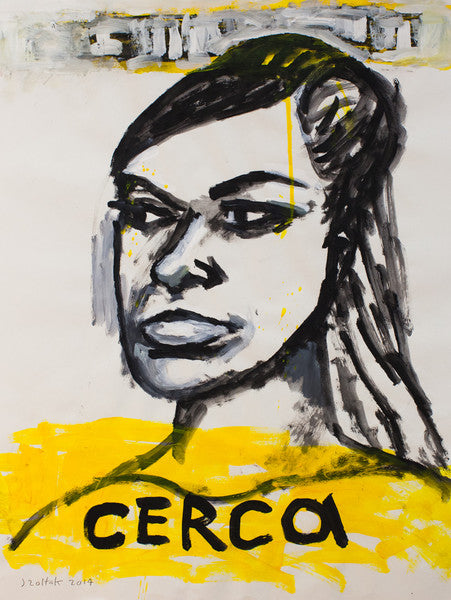

12 WOMEN AND A NIHILIST | Jack Zoltak

12 WOMEN AND A NIHILIST | Jack Zoltak

July 23 - September 6, 2015

Twelve Women and a Nihilist | Selected Works 2002 - 2015—the title of Jack Zoltak’s exhibition at These Days—represents the controversy of someone who does not believe in anything, surrounded by twelve women. With its metaphysical multiplication of life, it is an Expressionist version of Odysseus and the sirens, as told by a Romantic—a man who loves women, but who may not trust women. These thirteen mixed media paintings and drawings on paper, canvas, and wood each began with something seen, witnessed, or experienced in the “real world” and were then worked to a further degree of completion through memory and intuition. In them, reality, or the natural world, gives way to some other state of experience through the layered application of perception.

ARTIST STATEMENT

We live in a time of so many palatable, diverse visions, that it’s a challenge just to see ourselves. An artist has to sift through many options to try to find his or her voice; in reality, the voice has always been there. This challenge, finding one’s voice, is more difficult than developing and mastering technique.

For me, drawing and painting was a calling: first for political reasons, then for something deeper, something undefinable and more personal. One of Fellini’s characters speaking in Fellini’s stead, said, “I have nothing to say, and I feel compelled to say it.” Well, we know that Fellini had a lot to say, especially that art is a necessity to human existence, and the compulsion to say it is in part the affinity for the process of making art.

Philip Guston, an artist whom I have studied, is quoted as saying: “I’m not really interested in painting; I’m not interested in making a picture. Then what the hell am I interested in? I must be interested in the process I am talking about.” I am interested in both. The process, as I see it, is a way of interpreting the images and information that invade my senses every day. Making a “picture” is a way of coping with the beauty and brutality I witness daily, a way of diffusing their impact on my psyche. It is a way of possessing what we can’t have, of creating what we think we desire, of connecting with a viewer who will re-interpret the images we create and explain them to us. The world seems chaotic. In fact, Frank Gehry said that an American art born from our democracy will reflect a willingness to become comfortable living with chaos. I am embracing the seemingly disconnected imagery in my own work because that is how life feels to me at this point, the gap I see between ineffective politics and necessity. These factors are influencing me in a profound way. These conditions have led to a kind of suspension in which we as a nation are experiencing: Like a suspended chord in a musical composition creates a tension, we wait for the return of the reassuring melody.

The process of painting begins, for me, with a desire to work and then seeing something, usually someone, or a face that inspires me, call it impetus. Or I’ll smear a ground color on a surface, anything to get started, to make a mark of some kind.

I stare at the marks I’ve made on canvas or a piece of paper, the face, the shape, the initial image, and they are the beginning of a picture, or a record--Philip Guston called it “evidence”--and they suggest, they bring forth something hidden, something that needs to be expressed or revealed: a color, a texture, an impulse, other images, a word buried in memory. (There is something primal and eternal about making marks and spreading colors on a surface, whether that surface be the interior wall of a cave, a piece of Belgian linen, or the door of a discarded, abandoned refrigerator.) This is a repeating process as one works to create a piece. It is the visual equivalent of a poem, or a short story in a constant state of revision. It is a similar process that the Abstract Expressionists used, (and in fact, all painters have used, who have worked outside of some official established aesthetic). My process is similar, the difference being that recognizable imagery and the abstract marks must be integrated, so that they are all part of the whole and neither appears superfluous. In the end, the work must stand on its own, and contain a vitality that renders immaterial when it was created.